Is It A Perfect Crime By 1931 Standards?

Let's see what's in the Green Penguin postbag.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to this first edition of the revamped Shedunnit newsletter! If you've joined from one of our "farewell to social media" posts, then a particular hello. I hope this is going to be an enjoyable and sustainable way for us all to further our shared interest in golden age detective fiction. There will be newsletters four or five times a month, providing a mixture of background information about topics covered on the show, matters arising from the archive, reading recommendations and — as in this email — feedback and updates from listeners.

For the first seven "Green Penguin Book Club" podcast episodes, I included a postbag section at the end where I read out listeners' emails and comments. But this never quite felt satisfactory to me. Because these episodes only air every two months it felt like too long a gap since the last one for anyone to remember or care about the nuances of that conversation and it also made those episodes very long. Thus, the postbag is now moving to the newsletter and will come out a week after each Green Penguin episode airs.

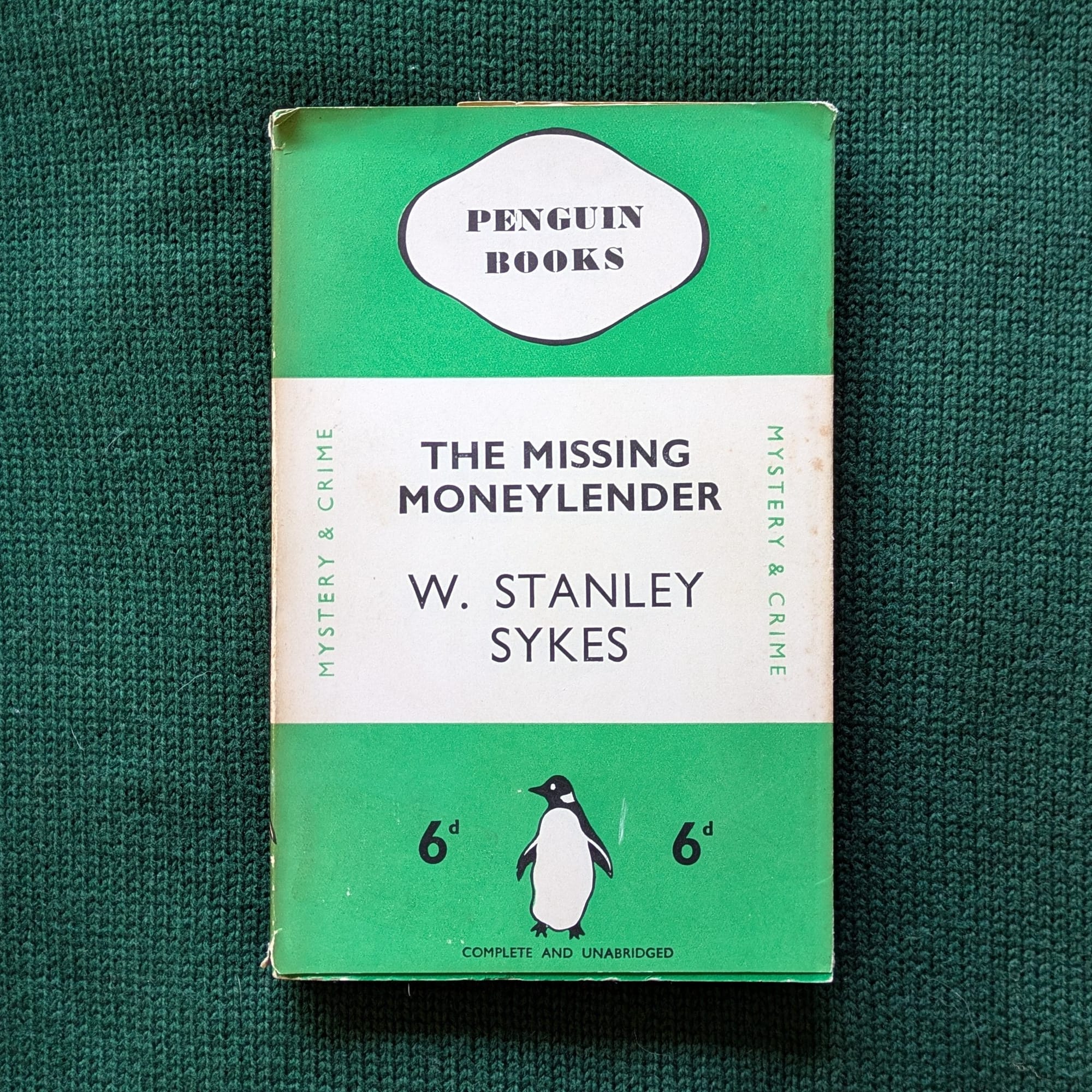

With the scene set, then, let's go through the Green Penguin Book Club postbag from the last couple of months. The episode about The Missing Moneylender by W. Stanley Sykes (Penguin 62) sparked some very interesting contributions, about everything from outdated murder methods and 20C insulin practices to true crime factoids. And I even heard from one listener about a Green Penguin spotted within a Green Penguin...

Even though Sarah is among those who was sadly unable to find a copy of The Missing Moneylender — it is unfortunately a rare book — she still tuned into our discussion and had this to say about the book's unique murder method:

"I was struck by the discussion of how the inclusion of early 20C science and technology made novels almost immediately out of date. Novels which stuck with more tried and trusted methods of death (arsenic, a blow on the back of the head) have definitely survived better. I wonder if the reference to electrical death was to These Names Make Clues, when the technicalities of the death are so baffling as to be impenetrable? E.C.R. Lorac did wisely return to coshes and guns in her next book, though there were some vague references to meddling with car engines, which she clearly didn’t really understand either!"

I agree: books that present a murder that is "unsolvable" simply because most people haven't yet heard of the technique used to kill tend to be less satisfactory to read decades later once that method is commonplace or even obsolete. I always chuckle when I'm reading a book or story from the very early 20C and the writer has to explain what "fingerprinting" is and why a criminal has been very canny to wear gloves.

The reference to an electrical death in that episode, though, was meant to be to Edgar Wallace's The Four Just Men. Famously, Wallace was so sure that nobody would guess his technological murder method in that book that he offered a financial reward to anyone would could write in with the correct answer. His offer was very badly worded, though, and he ended up having to pay everybody who got it right, not just the first correct entry, and it almost bankrupted him. There will be much more about this in the next Green Penguin Book Club episode at the end of May, because The Four Just Men happens to be the next Green Penguin in the series.

Fortunately for Shedunnit, we have listeners with backgrounds in toxicology and medicine to assist us in better understanding the science behind W. Stanley Sykes' baffling murder method. David, who studied toxicology as part of his degree, wrote in to help out:

"Especially in the early 1900s testing was limited and often destructive (some tests involved burning samples to observe flame colour, for example). An examiner would generally perform testing to confirm suspicions already in place — if they looked like they had been poisoned with arsenic you would test for arsenic, and so on. It was also difficult to determine the quantity of chemicals present in the body. These factors would lead a scientifically-minded killer to try one of three poisons:

1. A poison that rapidly degrades and changes chemical structure in the body, so is harder to identify.

2. A poison that in lower quantities is naturally present in the human body, so is harder to confirm as the cause of death.

3. A complex chemical compound that is both deadly and not recorded, so standard testing is not in place to detect it.

This is certainly illuminating for me when thinking about how a fictional murderer in the early 20C might go about committing an "undetectable" crime, and how a detective might counter their efforts.

On the scientific front, we also heard from Martin, a physician whose experience dates back fifty years. He gives some insight regarding the administering of insulin in particular, which is important to the plot of The Missing Moneylender:

"The original commercial insulin was derived from beef or pig pancreas. At the time of the book, there was only short acting insulin available as far as I know. People had to inject themselves 3 to 4 times a day and the amount of insulin was based upon testing urine for the presence of sugar, something that would occur in diabetics when the blood sugar was not well controlled.

Without reading the book, I can’t be sure what test they used for insulin, but I do know that, at the time of my residency in the middle 1970s, it was very difficult to test for exogenous, injected, insulin versus endogenous insulin. It certainly could’ve been a perfect crime in 1931.

Finally, safer blood transfusions were a recent phenomenon at that point. The ABO system was discovered about 1900 and the Rh system about 1940."

Good to know that the murder in The Missing Moneylender could have been a perfect crime by 1931 standards!

The sinister role that insulin played in this narrative led to a brief discussion of the true crime case involving Claus von Bülow from 1982. Listener Cherry writes in with a correction:

"In your recent discussion of medical murders, you mentioned the Claus von Bülow case in connection with insulin. He did not live on Long Island, as your guest speculated, but in Newport, Rhode Island (my hometown) in one of the magnificent mansions. Love your show!"

Thanks very much for that, Cherry — it's always good to hear from listeners who know the places the podcast covers much better than me.

On a more serious note, as part of our discussion of The Missing Moneylender my guest Moira Redmond and I looked at the antisemitic elements of the book. We noted that the level of antisemitism expressed in dialogue and thought by various characters aligned with what was unfortunately common at the time of publication (1931), but were surprised to find that the plot and structure of the book were not inherently antisemitic. By which I mean that the actual mechanism of the murder mystery did not depend on or relate to this prejudice.

However, Shedunnit Book Club member Wren pointed out an antisemitic trope that we missed in our conversation:

"I did find the antisemitism uncomfortable though not as pervasive as some others we’ve read. I was prepared for it, given the title (if he hadn’t been Jewish, it would have been 'the missing banker' rather than 'the missing moneylender'.) I think this was partly the opening scene with the comment, 'A Jew as a Jew is all right, but a Jew who pretends he is a gentile is a nasty bit of work.' This was followed by the discussion of him not paying the doctor’s bills.

I disagreed with Caroline's interpretation of this latter point. It may not have been attributed overtly to his being Jewish, but being a tightwad or not paying bills is a major antisemitic dog whistle. I’ve had more than one person use some variation of 'to Jew someone down' in my presence only to fall over themselves taking it back when they realized I was Jewish.

With that beginning, I was steeling myself for more of the same throughout, and was pleasantly surprised to find it was not a recurring theme, and (again as Caroline noted) the missing man was portrayed as a generally nice person and not as a blatant stereotype."

I found this insight very valuable, and a brilliant of example of how the Shedunnit Book Club helps me make a better podcast — I wasn't aware of this antisemitic dog whistle, and now I am. Thanks, Wren.

The final piece of mail today comes from Andrew. While reading Penguin #1182, Telling of Murder by Douglas Rutherford, he discovered something quite delightful and unexpected. Andrew writes:

"I found this reference to Green Penguins in a Green Penguin, 'Telling Of Murder', and I thought that it might interest you.

“ ‘Paddy,’ Diana said as I set the fresh glass in front of her. ‘I’ve been thinking. Can’t you and I do something together? I mean, you are a private detective. I’m sure the police are very good, but you might be able to do something by sort of – using your intuition.

She was looking very earnest and trusting; I liked the way her mouth stayed just a little bit open as she watched me. It gave her an eager expression.

‘You’ve been reading too many Green Penguins. Why, Maguire has just warned me to keep my nose clean. It doesn’t work out in real life like it does in detective stories, you know.’

She looked out of the window and the distress in her eyes caught me on a raw spot.”

Telling of Murder was first published in 1952. It's fascinating to see that in under 20 years the Green Penguin had become such a popular culture staple that authors were able to work mentions of it into their crime fiction with no explanation required. Do keep an eye out as you are reading; it would be great to find out what the earliest mention of a green penguin in a green penguin is!

Thank you very much for reading this. Do forward to a friend if you think they might be interested too. We'll be back next Wednesday with a newsletter all about the next new episode of Shedunnit, which is a profile of a lesser-known golden age writer. I wonder if you can guess who she might be?

Until next time,

Caroline

You can listen to every episode of Shedunnit at shedunnitshow.com or on all major podcast apps. Selected episodes are also available on BBC Sounds. There are also transcripts of all episodes on the website.